Key Concepts: Serial Position Effect; Primacy Effect; Recency Effect; Memorable Melodies; Strategic Breaks; 20-40 Rule

Summary: In any learning effort, the brain most easily remembers what it encountered at the beginning and end of the session. This is the serial position effect, and it can be found everywhere. How can we use this principle effectively: take strategic breaks!

All That Wasted Time!

You’re in a daze, surrounded by a mindless fog of confusion. You carefully peer into your thoughts, to find that you remember only half the events of the past 2 hours, if that much.

“What have I done?” you ask yourself.

2 hours ago, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, you were ready to do some learning. You were confident that the vast knowledge available to you would find fertile ground in your eager mind. Yet you closed that book, put down that guitar, or dropped your notes with only a fraction of the knowledge retained.

This happens to everyone. But what exactly happened?

Timing is Everything

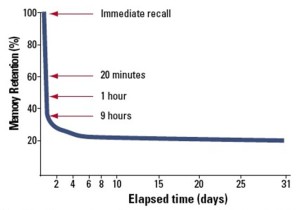

The reason is quite simple: You studied 2 hours straight. And (surprise!), you were doomed from the beginning. Unless you were raised by a vigilant cognitive psychologist, chances are you were never taught the crucial importance of timing. The human brain is simply not equipped to retain large amounts of minute information presented along such a long span of time.

This is why studying seems like such a pointless waste of time. So much work, but so little to show for it!

The Problem: The Serial Position Effect

Enter our old friend Herr Ebbinghaus, one of the fathers of modern memory psychology. The good doctor found two interesting phenomena during his sessions of memorizing series of syllables:

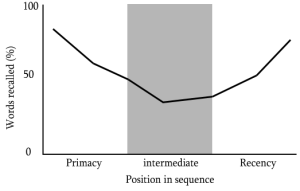

First, Ebbinghaus found that those syllables he studied at the beginning of each session were recalled much more readily than those that were studied later on. This phenomenon is known as the primacy effect.

Second, the doctor found that the syllables he studied at the end of each session were similarly easier to recall. This is known as the recency effect.

Taken together, the good doctor Ebbinghaus dubbed them the serial position effect. In a nutshell, we are more likely to remember what we encounter first and last in any period of concentration. Conversely, we are more likely forget whatever was in the middle.

The Serial Position Effect and Music: What Makes a Song Memorable

The serial position effect is why so many songs begin and end with simple themes. Consider “Hey Jude” by the Beatles. Try to remember the bones of the melody. As it happens, most people who have heard the song a few times will remember two basic things: the iconic “Hey Jude…” melody and the “Na, na, na, nananana…” tune. Not surprisingly, these are found at the beginning and end of this song. Listen to any iconic Beatles song and you’ll find that this is true for most of them. The Beatles instinctively understood the serial position effect and put it to industrious use.

This principle applies to many famous composers and musicians throughout history. Beethoven used the principle to great effect in his 5th Symphony. The serial position effect is one of the reasons why such a historical composition is remembered to this day. I encourage all of my readers to go back to their favorite pieces of music and explore this principle themselves.

The Solution: The 20-40 Rule

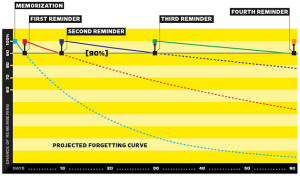

So how are we to harness this magnificent piece of knowledge we have just learned? Despite my dramatic subheading, there are no complex strategies involved: Take breaks often. Simply resting will tell your brain that there was a distinct beginning and end.

But there is the matter of timing. What is the optimum balance of concentration and rest? Thus far, there is very little concrete research done on this. I believe this is largely due to the media frenzy about decreased attention spans due to television and viral media. But in my experience, it’s a simple matter of trial and error.

In Use Your Head, Tony Buzan gives a general guideline I’ve always found useful for myself and my clients: focus for 20-40 minutes at a time, with 5-10 minute breaks in between. I call this the 20-40 Rule. The beauty of this “rule” is its flexibility. Certain things will be easier or harder to focus on depending on the person. If you are practicing some new music, you will probably be able to engross yourself for 40 whole minutes without losing your energy. But if you want to maximize your recall, you must make sure you take that 5-10 minute break.

In some situations, your brain will naturally want continuity. When practicing a speech or presentation, feel free to pause after each topic. When studying a textbook, take a break at each section. But when practicing a specific sports move, you will want to time your breaks to maximize your muscle memory. The same goes with practicing instruments; it is easy to lose track of time when you are doing something repetitive.

Conclusion: The Serial Position Effect is Everywhere

I wrote about the serial position effect in musical composition above. If you read any essay or article, the introduction and conclusion will always summarize the main points. The memorable conflicts and resolutions of many TV shows and sitcoms will be shown in the first 5 and final 5 minutes of the episode. One of the reasons books have chapters is so you will remember them better. When you think about an acquaintance, you will likely remember their first and final impressions. And so on, ad infinitum. After a short while, you will be able to easy observe the serial position effect everywhere. It’s that pervasive.

And in case you were wondering, yes, the serial position effect is one of the reasons why the Pomodoro Technique is so effective. But the principles of the technique go quite a bit deeper than that. In fact, an analysis of this technique will be useful in illustrating the basic principles of something we’ve only grazed in this article: Concentration and focus.